Wealth managers and Institutional investors routinely change managers once they have underperformed the market over the last two to three years, typically replacing them with funds or managers that recently outperformed. As fund selector, we are expected to apply the same principle, and in many instances, we do. Here, we will show that this standard procedure of firing losing managers and hiring winning managers based solely on their past three-year performance may lead to losses if not done knowledgeably. We will demonstrate that this strategy may be a necessary, but never a sufficient condition to succeed in selecting managers.

We backed this paper from an article by Rob Arnott, Vitali Kalesnik, Lillian Wu at Research Associates (see sources). The authors acknowledge that recently successful managers may have skill, but add that high alpha may often be the result of luck, and the turn out to be expensive holdings in a winning portfolio may typically set the stage for poor future performance. At the opposite, they highlight that recently disappointing managers often provide exposure to assets, factors, and strategies that have become inexpensive and, according to their research, are positioned for near-term success.

Firing recent winners and hiring recent losers

Abundant academic research demonstrates that the counterintuitive policy of firing recent winners and hiring recent losers, is a better way to invest than the conventional performance-chasing manager-selection rules. The authors point that Harvey and Liu (2017) demonstrate there is no repeatability in performance, which makes performance chasing in manager selection useless. Making matters worse, Cornell, Hsu, and Nanigian (2017) document mean reversion in mutual fund performance. The research by Arnott, Kalesnik and Wu aim to provide evidence that valuations are a key reason for this mean reversion under the argument that underperforming managers tend to hold cheaper assets, with cheaper factor loadings, setting them up for good subsequent performance, whereas recently winning managers tend to hold more-expensive assets. They show that investors can better identify funds likely to outperform in the future if they know 1) the return forecasts estimated for various factors, based on their relative valuations; and 2) the fund’s exposure to these various factors.

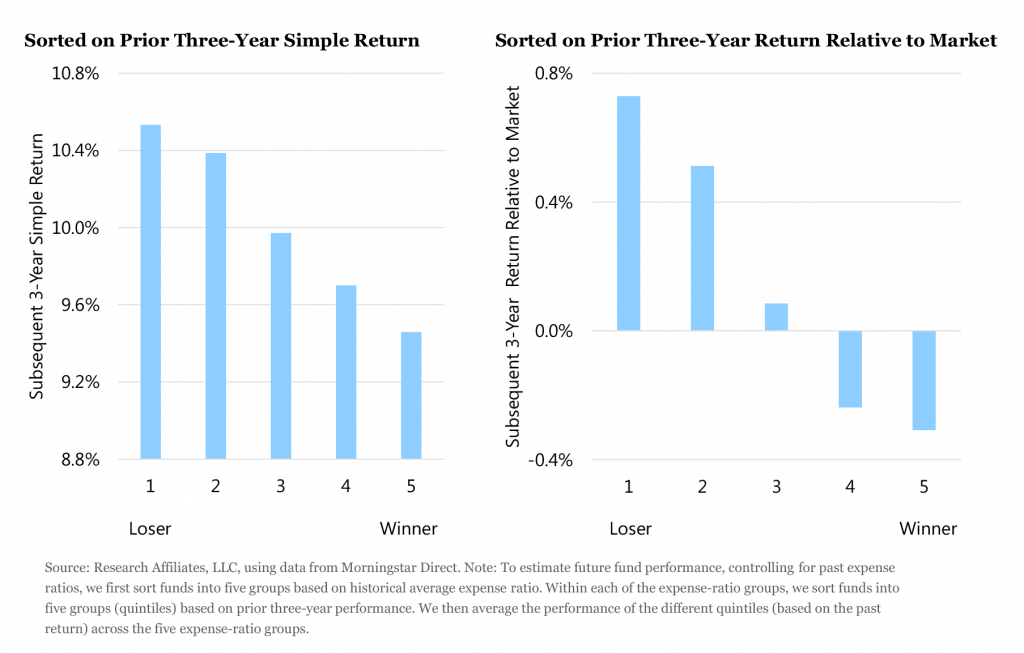

Mutual Fund Performance for Quintiles Based on Past Return, controlling for historical expense ratios, United States, Jan 1990 – Dec 2016

The decisive assumption made by the authors to support their finding is that investors evaluates past manager performance without adjusting for a manager’s style. Consequently, terminated managers will likely be dominated by representatives of underperforming styles, and they will most likely be replaced with a recently outstanding manager, representing a newly expensive style likely to underperform.

To note that at WSP, we evaluate past managers’ performance after adjusting for the managers’ style. Detecting style factors and isolating it from skills when assessing a manager’s performance has always been the foundation of our quantitative screening process. We aim to understand a style impact overtime, as well as its source. Does a style exposure is a consequence from a manager’s tactical allocation, a structural (lasting) style bias in the portfolio, or simply luck?

According to authors, underperforming strategies (or styles) often become cheap and might well be better candidates to receive new money, not terminated. For example, the Russell Value Index underperformed the market in the last three years of the tech bubble by a massive 2,400 basis points (bps), but was followed by 39% and 49% additional wealth generated by value versus the market in the next three and five years respectively.

Hence, if no adjustment is made for style, the top performing manager with assets at record-high-valuation relative to the market becomes a better candidate for termination than a manager who has recently disappointed with assets at exceptionally cheap relative valuation.

Combining past performance, style and relative valuations

It emphasises the importance to use a more elaborated screening process that combines past performance, style and current relative-valuation levels analysis. The decision will not always be to fire the losers and hire the winners, or vice versa. If a fund has outperformed (relative to its style bias), but the assets are not at newly rich valuation levels, that manager may worth to be considered for further allocation. Conversely, if a manager records bad performance relative to the market, and the assets have not become significantly cheaper, that’s bad news and, in most cases, this should be reasons for change.

Performance relative to peer group or style factors.

Overall, the study demonstrates mean reversion for simple return, and return relative to market (see chart above). Most importantly, the authors do not observe mean reversion in performance once they control for manager peer-group performance and manager style performance. This result comfort us in our belief that past (out)performance remains a relevant factor in managers’ selection, as long as you look after the right relative return (i.e., peer group or style factors relative returns).

To compute return relative to peer group variable, the authors subtract the average performance of all the funds in the group the fund belongs to (as identified by size and style) from the fund’s performance. The return relative to factor exposure is the most restrictive variable. They find a strong degree of persistence in performance after controlling for a comprehensive list of factor exposures.

Forward looking

The authors, highlighted rightly that, when allocating to fund managers, investors need to use a measure of expected fund returns that considers factor exposures, fees, manager skill in security selection, and factor expected returns estimated based on relative valuation.

They published a series of articles studying the link between factor valuations and factor subsequent performance (Arnott et al. [2016] and Arnott, Beck, and Kalesnik [2016 a, b]). The key point of the articles is that, just like individual asset classes or individual stocks, factors tend to perform better from a starting point of trading cheaply, and tend to perform worse after they become expensive.

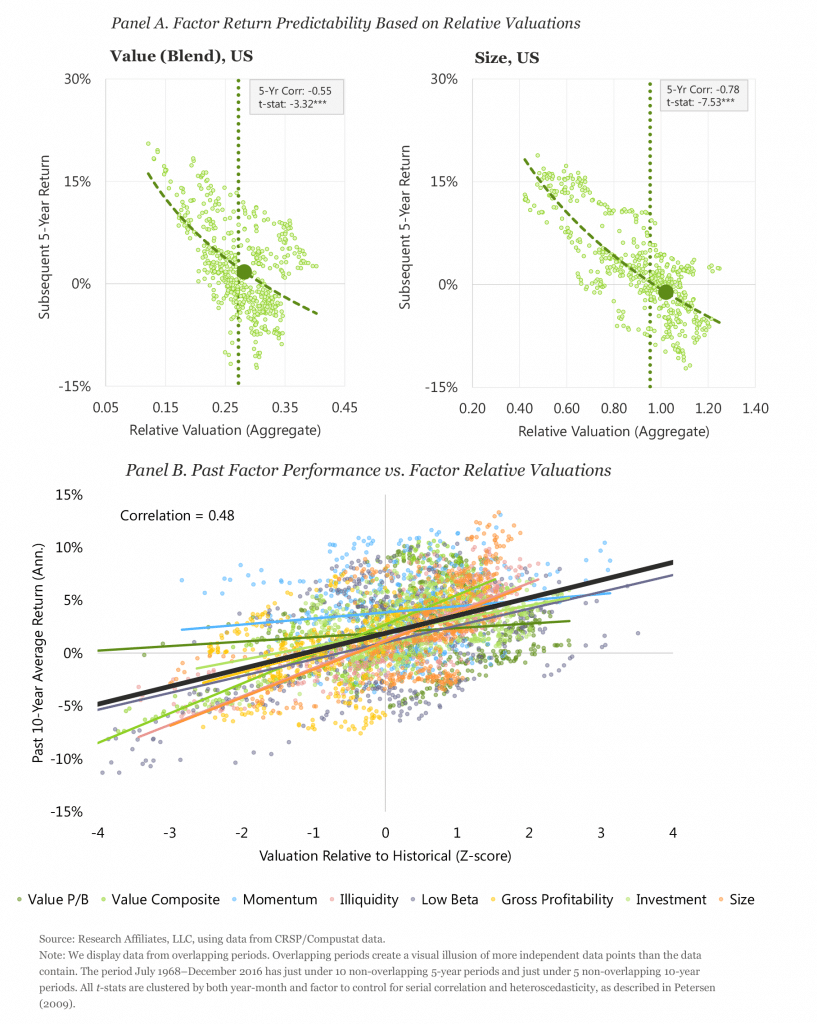

Two factors study chart

Reproduces the charts for two factors studied in their earlier work—value and size—showing the link between each factor’s relative valuation and its subsequent return.

Relative Valuations Forecast Subsequent Returns, United States, Jul 1968-Dec 2016

Source: Research Affiliates, September 2017

- Each factor is based on a long–short portfolio. Value is long a value portfolio, and short a growth portfolio; Size is long a small-cap portfolio, and short a large-cap portfolio.

- The relative valuation is based on the valuation of the long portfolio relative to the short portfolio. This relative valuation is a blend of four relative-valuation ratios: price to book, price to five-year average sales, price to five-year average cash flows, and price to five-year average dividends, each computed for the long portfolio relative to the short portfolio. The average valuation indicates whether the factor is trading cheap or rich relative to historical norms.

- For each point on Panel A, the position on the horizontal axis represents the starting relative valuation for the factor from some start date, while the vertical position shows the factor return over the following five years. The negative relationship between the valuation and subsequent return illustrates that as the factor gets cheap it tends to perform better; as it gets expensive it tends to perform worse.

- Although they only display the relationship for the value and size factors, the same relationship holds for most factors and strategies examined in the US, international, and emerging markets. For further details on this study, please refer to the source.

Understanding of the alpha generation and scenario dependency

The challenge for investors, and for us at WSP, is to gain a better understanding of the alpha generation and scenario dependency of a manager, and to develop a forward-looking analysis that never rely solely on past performance. We concur that relative valuations in factor has a predictive efficacy that can be exploited either by a fund manager with a mandate allowing it, or by investors allocating to managers having different styles. In the former case, if, and only if, a manager has proven to be successful in exploiting the relative valuation predictivity we have an objective reason to consider past performance to select, or inversely, fire a manager.